Gali's Legacy- Ancient Wisdom Set to Music

Gali Sanchez was a percussionist for Santana, Steve Winwood, and the Dave Matthews Band, amongst others. He rubbed elbows with some of the most famous musicians in modern music and is considered to be one of the best recorded conga players. But Gali Sanchez doesn’t care about any of that. In fact, he doesn’t even want to talk about it. What Gali wants to talk about is his purpose. “My calling is not what I thought it was when I was young,” says Gali, “my real calling has nothing to do with music, and everything to do with teaching.”

In the late 1990s Gali, feeling disillusioned with the music industry and mourning the loss of numerous friends to the rock and roll lifestyle, began to seek out more meaning in his life. “What saved me,” he says, “is when I got out of music and went back to traditional teaching and traditional values.”

The teaching and values he refers to are those of the Abenaki, a Native American tribe of northeastern North America. Gali’s mother went to powwow until she was 7, but as a member of what is referred to as “the boarding school generation” – a term that references the awful practice of separating Native American children from their families – she was removed from the culture of her people. Thus, Gali was raised with values of the Abenaki, but not with the traditions. It was he who reconnected with the tribe when left the music industry in 1998; and despite being diagnosed with prostate cancer the following year, he has dedicated the past 20 years to teaching others the Abenaki way of life, and to preserving Native American heritage.

Despite having only weeks left to live, Gali’s dedication to teaching others and sharing about the Native American way of life did not end when he came to Kline House. “I’m very pleased that I’ve been able to maintain a big part of my culture and my identity,” he says, “It makes things more comfortable and secure for me. I might only have a few weeks left, but I can still keep teaching.”

Since arriving at Kline House, Gali has taught about his culture with staff and visitors; his room is adorned with wampum and beaded medallions, and he has been able to maintain his spiritual practice. “I’m grateful,” says Gali, “It’s absolutely amazing.”

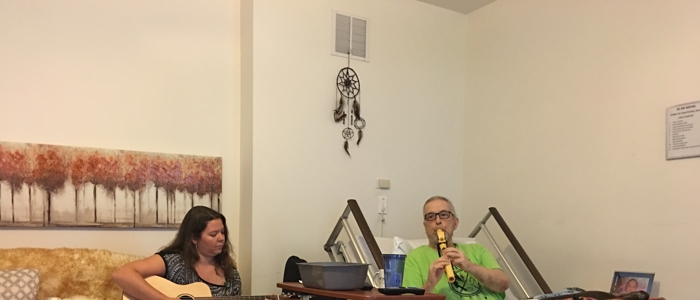

One of the things for which Gali is most grateful is the opportunity to work with our Music Therapist, Georgia Wells. They have been working together to put some of his poetry to music, with Georgia playing guitar and singing while Gali plays traditional handmade flutes. “What we did was magical,” he says. Georgia reflects, “One of the treasured secrets about music therapy is that, in its essence, it’s all about the relationship between the therapist and the participant(s). Our sessions together illustrate that beautifully.” She explains, “Music is often a foot in the door, or an avenue that affords opportunity for connection, or relief… and in Gali’s case, it is the vessel through which he can fulfill his mission to teach, to honor, and to perpetuate his story, and the story of his people. It has been a privilege to learn from him.” Gali and Georgia are in the process of recording several of his works. It will be something to leave as one last lesson; one last legacy.

Through his music, activism, and teaching, Gali has touched countless lives. We know that even after he is gone Gali will continue to reach hearts and change minds, and we are honored to have helped with any small part of that.